Techno Dystopia in 500 Meters, Part II

"One Goal, One Goal Only, For All Of Us - Perfection!"

Part I. here

Part II. At the Restaurant

“Do you need help?” asked my friend, sitting across from me at the table.

“Yes, I want a Diet Coke but I don’t know how to work this thing,” I said as I handed the tablet over to her.

Ever since the increasing minimum wage and stringent labor laws made it harder for restaurants to hire human employees, ordering-via-tablet has become a widespread solution in Korea.

My friend juggled the interface for half a minute.

“Ah! You need to select a cup for the soda. There, I ordered it,” she said with a smile to ease my frustration. Her slightly puffy double-eyelids that she recently got done squinted in a perfect crescent moon-shape as she smiled.

A few moments later, a Servbot reeled in to bring us food and my Diet Coke. The bot had shelves attached to a supporting beam, looking like ribs attached to a spine. As I took our food from its trays, “thank you,” it chirped in a baby-voice, winking with its pixel-eyes from a screen above its beam. A robotic skeleton that even acted cute.

As I was silently mulling over the freakishness of the machine, one of my friends, mom to a 10 year-old boy, made a comment that threw me off.

“The doctor says that my son is well on his way to reach his target height. So I’m thinking about stopping his hormone therapy. I don’t want him to be too tall either,” my friend said.

“What? Hormone therapy? What’s wrong with him?” I asked, surprised and concerned.

“Nothing wrong. Kids these days all grow so tall. So I’m giving him growth hormone injections. I don’t want him to live with the insecurity of being shorter than everyone else,” she replied.

I fell silent.

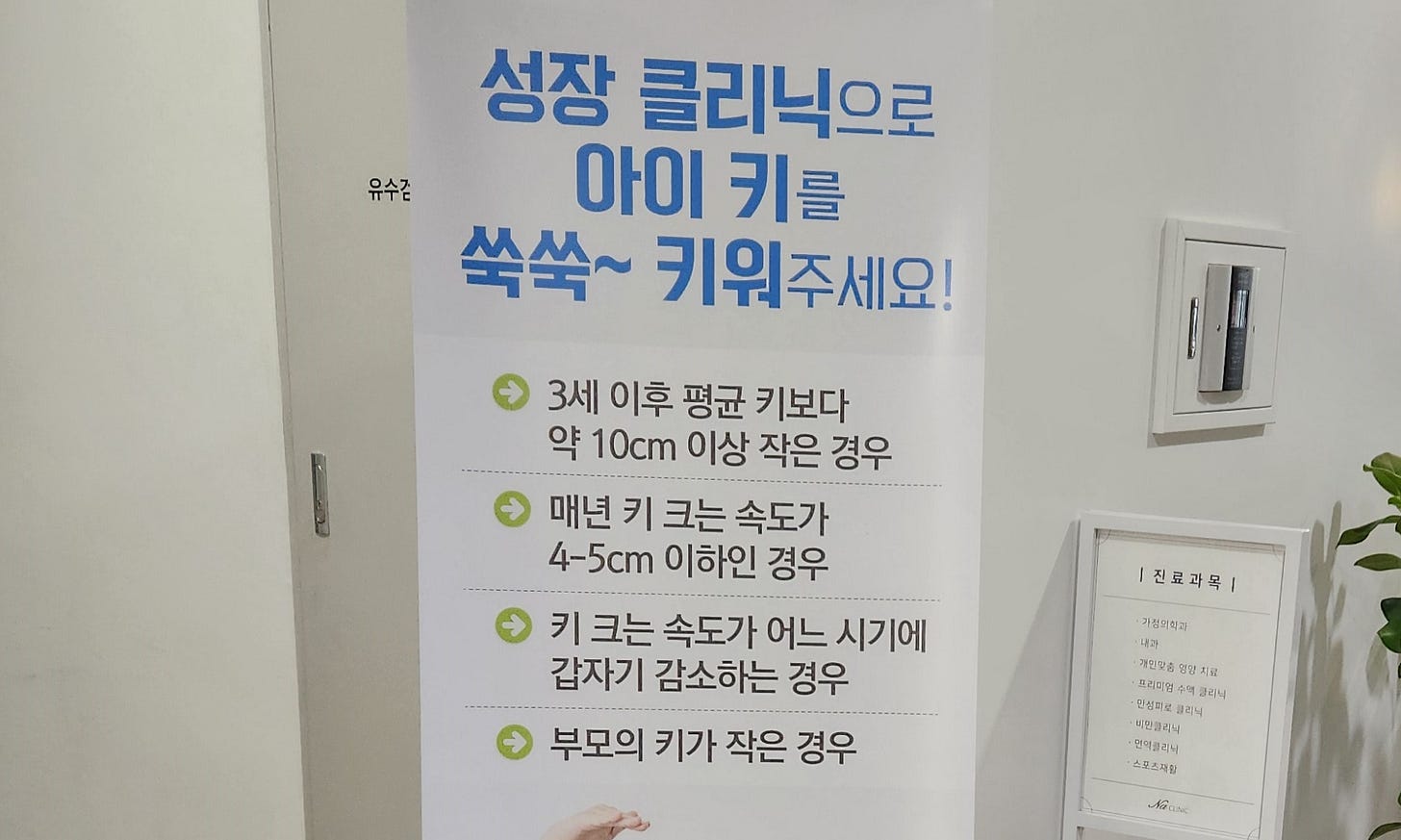

Nowadays, thanks to medical technology, doctors can allegedly predict the exact height a child will grow to. And moms give growth hormone therapies (GHT) to their children as early as age 3-4 if they deem the projected height to be less than confidence-boosting.

As per advertisement:

Increase your child’s height with growth therapy if:

- Your child is above age 3 and 10 cm shorter than children of the same age.

- Your child grows by less than 4-5 cm per year.

- Your child’s growth speed abruptly slows down.

- The parents’ heights are short.

Growing up with 4 brothers, I saw how boys could grow like bamboo trees in their teenage years. So hesitantly, I replied, especially since my friend and her husband were of normal heights:

“Aren’t there long-term side effects to interfering with a healthy kid’s endocrine system? I mean, especially at such a young age… And when did doctors become prophets?”

“Everyone is doing it,” my friend said strongly. I detected an undertone of irritation in her voice, which immediately made me regret speaking out. In our Confucianism-rooted culture, fitting in with the group is an essential social currency. Oftentimes more important than exhibiting personal characteristics. It was important to my friend that her son didn’t lag behind others.

“Besides, I see the results already. It’s totally effective,” she continued.

I’m not a mom. So I am a stranger to the world of child optimization. At first, I thought that this growth therapy was a rare endeavor, occasionally carried off by some exceptionally-competitive parents. But subsequently, on multiple occasions, other parents also spoke about their own children’s GHT. So I inquired about it to a relative, mom to a 4 year-old boy, who informed me that she was one of the rare people in her social circle to reject the therapy. GHT is a fast-growing treatment in South Korea.

Engineering children… I tried to hide the shock but I couldn’t. And I thought about how GHT could soon become the norm in Korea, just like plastic surgery. Because as my friend said, “it’s totally effective.”

I also couldn’t stop thinking about how the stories that served as warnings in 20th century dystopian novels have now become stories to be worried about. Take This Perfect Day (1970) for example. The author, Ira Levin, imagined a world of perfect order, beauty and efficiency, controlled by a central computer - UniComp. Citizens of this world (called ‘members’) are genetically enhanced to look homogeneously beautiful, and - with the exception of a hidden ruling class of UniComp programmers - receive routine drug and hormone treatments, as prescribed by the computer. The treatments keep the members free of illnesses, but also sterilize them with contraceptives, and deprive them of their thoughts, feelings and desires with tranquilizers. For perfect order to exist, outstanding characteristics cannot. Every aspect of the members’ lives is, therefore, also controlled - what they do, what they’re called, what they eat, who they marry, when they have sex, when they die. It is a utopia, free of ugliness, disease, poverty, crime, war and hunger, but also of individualism. A world free of things, but not free to do things.

“Because everyone is doing it”… my friend had said. Since South Korea is a particularly competitive society, also placing remarkable importance on appearance, it was as if my friend, obeying the principles of society with her humble and good nature, couldn’t consider the freedom of opting out of GHT.

A particular quote in the novel also resonated with the situation. Wei, the overlord of UniComp, says:

“If nothing could be done about it [physical imperfection], then you would be justified in accepting it. But an imperfection that can be remedied? That, we must never accept. One goal, one goal only, for all of us - perfection.”

But limitless pursuit of perfection is bound to end in self-destruction. In the novel, [spoiler alert] Wei accepts Chip, the protagonist, as one of the programmers and quickly appoints him as a High Council member because of his courage and intelligence. But Wei is duped by Chip’s ruse. Chip ends up destroying UniComp to save humanity from Wei’s techno-tyranny.

This Perfect Day is a fiction written half a century ago. But it presents uncanny similarities to our reality today. Our unbounded effort to perfect physical appearance seems to destroy something about what it means to be human. It insinuates that we are nothing more than some display dolls, with nothing special beyond our appearances. Mere automata that can be subdued or augmented with pharmacological substances.

Therefore, I found cruelty in conditioning a child to believe that he would be a better person a few centimeters taller. That the way he is born is unacceptable. It was an act of presuming that his happiness could not come from his natural self, but only from obtaining what others oblige him to want, and only from homogenising with others.

And similarly to the totalitarian perfection of the novel, the pursuit of perfection in our world is not limited to physical appearance either. As seen in Gwanghwamun, corporations attempt to perfect their wheels of production-consumption with omnipresent advertisements. And the government its control with proliferating surveillance cameras.

Did I ever mention that I once got called out on a PA for walking my dog unleashed in an empty park in Seoul? “LEASH YOUR DOG. OR YOU WILL BE FINED,” the high and mighty PA shouted from the void. I was alone in that park.

With technology, nothing has become impossible. Even brain chips are now available to perfect human performance. And in the process of obsessing over perfection, virtues that humans have valued through millennia of existence seem to fade away: freedom, purpose, honor, meaning…

“You are such an I,” another friend said to me at the end of our conversation.

“I’m what?” I was perplexed.

“I. MBTI.”

“Ah…”

Short for Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, MBTI is a personality test that qualifies a person’s character in a combination of 4 letters, like ‘INFJ’:

⬝ Introverted

⬝ iNtuitive

⬝ Feeling

⬝ Judging

According to MBTI, humans can be circumscribed into a matrix of 16 personality types. And it is a wildly popular way of gauging someone’s character in Korea, perhaps because of its simplicity.

“What are you anyway?” asked my friend.

“I don’t know. It changed every time I took the test. I think it’s bullshit anyway,” I said sullenly with my spirit visibly broken.

“You’re definitely a T,” said my friend sternly with decision.

‘T’ stands for ‘Thinking,’ I was informed. How absurd… An innate human ability, which distinguishes us from animals, is now considered a particular personal trait. So I just shrugged my shoulders and gave a forced smile. It upset me that my existence had become a foregone conclusion, so succinctly summarized by a single alphabet.

After dinner, as I walked back home, I thought about how in every dystopian novel that I have thus far read, there was always a land of outcasts, where people remained dirty and violent, but free. Anguished but free. And I entertained the idea of exiting this techno-dystopia and moving to the middle of the Amazonian jungle to live like a bushman. How meaningful would my life be if I were to live as one with nature, away from this techno-nonsense!

A deluded fantasy. Never mind that I wouldn’t last a few days in the jungle, it also quickly hit me that if the world was to go back to the bushman era, it would end up exactly where we are now a few millennia later. Because this world was a better option. Thinking that everything would be fine if I only did away with technologization was as dystopian as GHT.

But paradoxically, having these thoughts, as depressing as they sound, also gave me some relief. I felt reassured that my happiness didn’t come from elsewhere than from within my own consciousness. Feeling suffocated was proof that I had my own thoughts, my own feelings, my own identity. Proof that I was a unique being.

And that felt like a refuge. My personal agency.

Lost in my thoughts, I crossed a street without realizing that I was jaywalking. A car honked loudly. Startled, I turned my head around. And I saw a bright green compact minibus with pitch-black windows. On the side of the vehicle was written “Driverless Bus Testing.” A machine had just gotten angry at me because I was in its way.

I wanted to blow my own horn back by growling some vulgarities at it, but I didn’t.

Teaching human emotions to a machine would only lead to its perfection.

Loved it, Jisoo. "I felt reassured that my happiness didn’t come from elsewhere than from within my own consciousness." -- this, in particular, may be the essence of it all. :)

Jisoo! Sometimes, especially in recent years, I feel this surreal sensation that I’m a person of the past living in the future, not only terms of physical environment, but also in values. When I read your essays it reminds me that I’m not the only one feeling this :’) A voice like yours against the “dystopian mainstream” is so important to be heard! Thank you for sharing